When Did Mt St Helens Erupted When Will Mt St Helens Erupt Again

| 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens | |

|---|---|

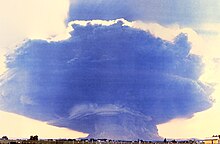

Photograph of the eruption column, May 18, 1980 | |

| Volcano | Mount St. Helens |

| Start date | March 27, 1980 (1980-03-27) [1] |

| Start fourth dimension | 8:32 a.m. PDT |

| Type | Phreatic, Plinian, Peléan |

| Location | Skamania Canton, Washington, U.S. 46°12′1″North 122°xi′12″W / 46.20028°Northward 122.18667°W / 46.20028; -122.18667 Coordinates: 46°12′1″N 122°xi′12″W / 46.20028°N 122.18667°W / 46.20028; -122.18667 |

| VEI | five[1] |

| Impact | Approximately 57 deaths, nigh $ane.1 billion in belongings damage (or $3.6 billion today, adjusted for aggrandizement); caused a plummet of the volcano'south northern flank, deposited ash in 11 U.South. states and v Canadian provinces |

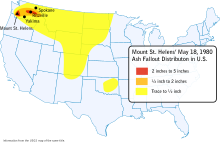

Map of eruption deposits | |

On March 27, 1980, a series of volcanic explosions and pyroclastic flows began at Mount St. Helens in Skamania County, Washington, United States. A serial of phreatic blasts occurred from the summit and escalated until a major explosive eruption took place on May eighteen, 1980, at eight:32 AM. The eruption, which had a Volcanic Explosivity Index of 5, was the most pregnant to occur in the contiguous The states since the much smaller 1915 eruption of Lassen Elevation in California.[ii] It has oftentimes been declared the nigh disastrous volcanic eruption in U.S. history.

The eruption was preceded past a 2-month series of earthquakes and steam-venting episodes caused by an injection of magma at shallow depth beneath the volcano that created a big burl and a fracture arrangement on the mount's north gradient. An earthquake at 8:32:11 am PDT (UTC−7) on Sunday, May 18, 1980,[3] caused the entire weakened n face up to slide away, creating the largest subaerial landslide in recorded history.[iv] This allowed the partly molten rock, rich in loftier-pressure gas and steam, to all of a sudden explode n toward Spirit Lake in a hot mix of lava and pulverized older rock, overtaking the landslide. An eruption column rose eighty,000 anxiety (24 km; xv mi) into the temper and deposited ash in 11 U.Due south. states[5] and various Canadian provinces.[half-dozen] At the same time, snowfall, water ice, and several entire glaciers on the volcano melted, forming a series of large lahars (volcanic mudslides) that reached as far equally the Columbia River, nearly 50 miles (80 km) to the southwest. Less astringent outbursts connected into the side by side day, just to be followed by other large, but not equally subversive, eruptions later that twelvemonth. Thermal energy released during the eruption was equal to 26 megatons of TNT.[7]

Near 57 people were killed, including innkeeper and World State of war I veteran Harry R. Truman, photographers Reid Blackburn and Robert Landsburg, and geologist David A. Johnston.[viii] Hundreds of square miles were reduced to wasteland, causing over $ane billion in damage (equivalent to $3.6 billion in 2021), thousands of animals were killed, and Mount St. Helens was left with a crater on its north side. At the time of the eruption, the summit of the volcano was owned by the Burlington Northern Railroad, merely later on, the railroad donated the land to the United States Woods Service.[ix] [10] The area was later preserved in the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument.

Mount St. Helens from Monitor Ridge, this prototype shows the cone of devastation, the huge crater open to the north, the posteruption lava dome inside, and Crater Glacier surrounding the lava dome. The small photo on the left was taken from Spirit Lake before the eruption and the small photo on the correct was taken after the eruption from roughly the aforementioned place. Spirit Lake can too exist seen in the larger paradigm, equally well as two other Pour volcanoes.

Build-up to the eruption [edit]

Mount St. Helens remained dormant from its last flow of action in the 1840s and 1850s until March 1980.[11] Several small-scale earthquakes, beginning on March fifteen, indicated that magma might accept begun moving beneath the volcano.[12] On March 20, at 3:45 pm Pacific Standard Time (all times are in PST or PDT), a shallow, magnitude-4.2 earthquake centered beneath the volcano'due south north flank,[12] signaled the volcano's render from 123 years of hibernation.[13] A gradually building earthquake swarm saturated area seismographs and started to climax at almost apex on March 25, reaching meridian levels in the next 2 days, including an earthquake registering v.1 on the Richter calibration.[14] A total of 174 shocks of magnitude 2.6 or greater was recorded during those ii days.[15]

USGS photograph showing a preavalanche eruption on April 10

Shocks of magnitude 3.ii or greater occurred at a slightly increasing rate during Apr and May, with five earthquakes of magnitude 4 or above per day in early on April, and eight per 24-hour interval the week before May xviii.[thirteen] Initially, no directly sign of eruption was seen, merely small earthquake-induced avalanches of snow and ice were reported from aerial observations.

At 12:36 pm on March 27, phreatic eruptions (explosions of steam caused by magma of a sudden heating groundwater) ejected and smashed rock from inside the old summit crater, excavating a new crater 250 feet (75 m) wide,[13] [16] [17] [18] and sending an ash column about 7,000 feet (2.i km) into the air.[15] By this date, a sixteen,000-foot-long (iii.0 mi; 4.nine km) eastward-trending fracture system had as well developed across the pinnacle area.[19] This was followed by more earthquake swarms and a series of steam explosions that sent ash 10,000 to 11,000 feet (3,000 to 3,400 m) above their vent.[xiii] Most of this ash fell between 3 and 12 mi (5 and 19 km) from its vent, but some was carried 150 mi (240 km) south to Bend, Oregon, or 285 mi (460 km) due east to Spokane, Washington.[twenty]

A 2d, new crater and a blue flame were observed on March 29.[20] [21] The flame was visibly emitted from both craters and was probably created by burning gases. Static electricity generated from ash clouds rolling downward the volcano sent out lightning bolts that were up to two mi (three km) long.[20] Ninety-three separate outbursts were reported on March thirty,[20] and increasingly strong harmonic tremors were first detected on April 1, alarming geologists and prompting Governor Dixy Lee Ray to declare a state of emergency on Apr iii.[21] Governor Ray issued an executive order on Apr 30 creating a "carmine zone" around the volcano; anyone caught in this zone without a pass faced a $500 fine (equivalent to $1,600 today) or half-dozen months in jail.[22] [23] This precluded many motel owners from visiting their property.[24]

By Apr seven, the combined crater was one,700 by 1,200 ft (520 by 370 k) and 500 ft (150 k) deep.[25] A USGS team adamant in the concluding calendar week of Apr that a 1.5 mi-diameter (2.4 km) section of St. Helens' due north face was displaced outward past at to the lowest degree 270 ft (82 m).[19] For the rest of Apr and early on May, this bulge grew past 5 to 6 ft (1.5 to 1.eight one thousand) per day, and by mid-May, it extended more than 400 ft (120 m) north.[19] As the bulge moved northward, the peak expanse backside information technology progressively sank, forming a complex, down-dropped cake called a graben. Geologists announced on Apr 30 that sliding of the bulge area was the greatest immediate danger and that such a landslide might spark an eruption.[23] [26] These changes in the volcano'due south shape were related to the overall deformation that increased the volume of the volcano past 0.03 cu mi (0.13 kmthree) by mid-May.[27] This book increase presumably corresponded to the volume of magma that pushed into the volcano and deformed its surface. Because the intruding magma remained below ground and was not directly visible, it was chosen a cryptodome, in contrast to a truthful lava dome exposed at the surface.

On May 7, eruptions similar to those in March and April resumed, and over the post-obit days, the bulge approached its maximum size.[28] All activeness had been confined to the 350-year-old summit dome and did not involve any new magma. Near 10,000 earthquakes were recorded earlier the May xviii issue, with most concentrated in a modest zone less than 1.6 mi (2.half-dozen km) directly beneath the bulge.[27] Visible eruptions ceased on May 16, reducing public interest and consequently the number of spectators in the area.[29] Mounting public pressure then forced officials to allow fifty carloads of property owners to enter the danger zone on Saturday, May 17, to gather whatever property they could carry.[29] [30] Some other trip was scheduled for 10 am the next day,[29] [30] and because that was Sunday, more than 300 loggers who would unremarkably be working in the surface area were not there. By the time of the climactic eruption, dacite magma intruding into the volcano had forced the north flank outward nearly 500 ft (150 m) and heated the volcano's groundwater system, causing many steam-driven explosions (phreatic eruptions).

Landslide and climactic phase [edit]

Sequence of events on May 18

Lakes nearest to Mount St. Helens have been partly covered with felled trees for more than twoscore years. This photograph was taken in 2012.

North Fork Toutle River valley filled with landslide deposits

As May eighteen dawned, Mount St. Helens' activeness did not show whatsoever alter from the pattern of the preceding calendar month. The rates of bulge movement and sulfur dioxide emission, and ground temperature readings did non reveal whatsoever changes indicating a catastrophic eruption. USGS volcanologist David A. Johnston was on duty at an ascertainment mail around half-dozen mi (10 km) north of the volcano: as of half dozen:00 am, Johnston's measurements did not bespeak any unusual action.[9]

At 8:32 am, a magnitude-5.1 earthquake centered straight below the northward gradient triggered that part of the volcano to slide,[31] approximately vii–20 seconds subsequently the shock.[9] The landslide, the largest in recorded history, traveled at 110 to 155 mph (177 to 249 km/h) and moved beyond Spirit Lake's westward arm. Part of it hit a ane,150 ft-high (350 m) ridge about 6 mi (ten km) due north.[9] Some of the slide spilled over the ridge, but most of information technology moved 13 mi (21 km) down the N Fork Toutle River, filling its valley up to 600 feet (180 k) deep with avalanche debris.[31] An expanse of about 24 sq mi (62 kmtwo) was covered, and the full volume of the eolith was about 0.7 cu mi (2.9 km3).[9]

Scientists were able to reconstruct the motion of the landslide from a series of rapid photographs by Gary Rosenquist, who was camping 11 mi (18 km) abroad from the blast.[9] Rosenquist, his political party, and his photographs survived because the boom was deflected by local topography 1 mi (1.6 km) short of his location.[32]

Almost of St. Helens' former due north side became a rubble deposit 17 mi (27 km) long, averaging 150 ft (46 g) thick; the slide was thickest at ane mi (1.six km) below Spirit Lake and thinnest at its western margin.[9] The landslide temporarily displaced the waters of Spirit Lake to the ridge northward of the lake, in a behemothic wave about 600 ft (180 m) high.[33] This, in turn, created a 295 ft (ninety g) barrage of debris consisting of the returning waters and thousands of uprooted trees and stumps. Some of these remained intact with roots, but most had been sheared off at the stump seconds earlier past the smash of superheated volcanic gas and ash that had immediately followed and overtaken the initial landslide. The debris was transported along with the water as it returned to its bowl, raising the surface level of Spirit Lake by about 200 ft (61 m).[9]

4 decades afterwards the eruption, floating log mats persist on Spirit Lake and nearby St. Helens Lake, changing position with the air current. The rest of the trees, especially those that were not completely discrete from their roots, were turned upright by their own weight and became waterlogged, sinking into the muddy sediments at the lesser where they are in the process of becoming petrified in the anaerobic and mineral-rich waters. This provides insight into other sites with a similar fossil record.[34]

Pyroclastic flows [edit]

Initial lateral blast [edit]

Calculator graphics showing the May 18 landslide (green) being overtaken by the initial pyroclastic catamenia (scarlet)

The landslide exposed the dacite magma in St. Helens' neck to much lower pressure, causing the gas-charged, partially molten stone and loftier-force per unit area steam higher up it to explode a few seconds afterwards the landslide started. Explosions burst through the trailing part of the landslide, blasting stone debris northward. The resulting blast directed the pyroclastic flow laterally. It consisted of very hot volcanic gases, ash, and pumice formed from new lava, besides as pulverized old rock, which hugged the ground. Initially moving about 220 mph (350 km/h), the smash speedily accelerated to effectually 670 mph (one,080 km/h), and it may have briefly passed the speed of audio.[9] [31]

Pyroclastic flow material passed over the moving barrage and spread outward, devastating a fan-shaped area 23 miles across past 19 miles long (37 km × 31 km).[31] In total, well-nigh 230 sq mi (600 km2) of forest were knocked down,[31] and extreme heat killed trees miles across the blow-down zone. At its vent, the lateral blast probably did non final longer than about 30 seconds, but the northward-radiating and expanding blast cloud connected for about another minute.

Superheated flow material flashed water in Spirit Lake and North Fork Toutle River to steam, creating a larger, secondary explosion that was heard every bit far away equally British Columbia,[35] Montana, Idaho, and Northern California, nevertheless many areas closer to the eruption (Portland, Oregon, for example) did not hear the boom. This so-chosen "quiet zone" extended radially a few tens of miles from the volcano and was created by the complex response of the eruption's sound waves to differences in temperature and air motion of the atmospheric layers, and to a lesser extent, local topography.[9]

Subsequently studies indicated that i-third of the 0.045 cu mi (0.19 kmiii) of cloth in the flow was new lava, and the residuum was fragmented, older stone.[35]

Lateral blast result [edit]

Photographer Reid Blackburn's Volvo after the eruption

Many trees in the direct nail zone were snapped off at their bases and the globe was stripped and scorched.

The huge ensuing ash deject sent skyward from St. Helens' northern human foot was visible throughout the quiet zone. The near-supersonic lateral boom, loaded with volcanic droppings, caused devastation as far equally nineteen mi (31 km) from the volcano. The area affected by the blast tin can be subdivided into roughly concentric zones:[nine]

- Direct blast zone, the innermost zone, averaged about viii mi (xiii km) in radius, an expanse in which virtually everything, natural or artificial, was obliterated or carried away.[9] For this reason, this zone besides has been called the "tree-removal zone". The flow of the material carried past the blast was not deflected by topographic features in this zone. The blast released free energy equal to 24 megatons of TNT.

- Channelized blast zone, an intermediate zone, extended out to distances equally far as 19 mi (31 km) from the volcano, an surface area in which the flow flattened everything in its path and was channeled to some extent past topography.[9] In this zone, the forces and direction of the smash are strikingly demonstrated by the parallel alignment of toppled large copse, broken off at the base of the body equally if they were blades of grass mown by a scythe. This zone was too known as the "tree-down zone". Channeling and deflection of the blast acquired strikingly varied local furnishings that notwithstanding remained conspicuous after some decades. Where the blast struck open state directly, it scoured it, breaking trees off brusque and stripping vegetation and fifty-fifty topsoil, thereby delaying revegetation for many years. Where the blast was deflected then every bit to pass overhead by several metres, information technology left the topsoil and the seeds it contained, permitting faster revegetation with scrub and herbaceous plants, and later with saplings. Trees in the path of such college-level blasts were cleaved off wholesale at diverse heights, whereas nearby stands in more than sheltered positions recovered comparatively apace without conspicuous long-term harm.

- Seared zone, also called the "standing dead" zone, the outermost fringe of the impacted area, is a zone in which trees remained standing, but were singed brown by the hot gases of the blast.[nine]

Volcanologist David A. Johnston (photographed on April 4, 1980) was among the approximately 57 people killed in the eruption.

Past the time this pyroclastic flow striking its start human victims, it was still as hot as 680 °F (360 °C) and filled with suffocating gas and flying debris.[35] Most of the 57 people known to have died in that twenty-four hours's eruption succumbed to asphyxiation, while several died from burns.[ix] Order possessor Harry R. Truman was buried under hundreds of feet of barrage material. Volcanologist David A. Johnston was i of those killed, as was Reid Blackburn, a National Geographic photographer. Robert Landsburg, another photographer, was killed past the ash cloud. He was able to protect his film with his torso, and the surviving photos provided geologists with valuable documentation of the historic eruption.[36]

Later flows [edit]

Subsequent outpourings of pyroclastic material from the alienation left by the landslide consisted mainly of new magmatic debris rather than fragments of pre-existing volcanic rocks. The resulting deposits formed a fan-like pattern of overlapping sheets, tongues, and lobes. At least 17 split up pyroclastic flows occurred during the May 18 eruption, and their amass volume was almost 0.05 cu mi (0.21 km3).[ix]

The flow deposits were still at almost 570 to 790 °F (300 to 420 °C) two weeks after they erupted.[nine] Secondary steam-blast eruptions fed past this estrus created pits on the northern margin of the pyroclastic-flow deposits, at the s shore of Spirit Lake, and forth the upper role of the North Fork Toutle River. These steam-boom explosions continued sporadically for weeks or months later the emplacement of pyroclastic flows, and at least one occurred a yr later, on May 16, 1981.[9]

Ash column [edit]

The ash deject produced by the eruption, as seen from the village of Toledo, Washington, 35 miles (56 km) to the northwest of Mount St. Helens: The cloud was roughly 40 mi (64 km) wide and xv mi (24 km; 79,000 ft) high.

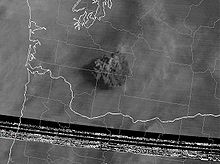

Ash deject from Mt. St. Helens equally captured past the GOES 3 conditions satellite at 15:45 UTC.

As the avalanche and initial pyroclastic flow were still advancing, a huge ash column grew to a meridian of 12 mi (19 km) higher up the expanding crater in less than 10 minutes and spread tephra into the stratosphere for 10 direct hours.[35] About the volcano, the swirling ash particles in the temper generated lightning, which in turn started many wood fires. During this fourth dimension, parts of the mushroom-shaped ash-cloud column collapsed, and savage back upon the earth. This fallout, mixed with magma, mud, and steam, sent boosted pyroclastic flows speeding down St. Helens' flanks. Later, slower flows came directly from the new north-facing crater and consisted of glowing pumice bombs and very hot pumiceous ash. Some of these hot flows covered ice or water, which flashed to steam, creating craters up to 65 ft (xx k) in diameter and sending ash as much every bit six,500 ft (2,000 m) into the air.[37]

Potent, high-altitude wind carried much of this textile east-northeasterly from the volcano at an average speed around 60 miles per hour (100 km/h). By nine:45 am, it had reached Yakima, Washington, 90 mi (140 km) away, and by eleven:45 am, information technology was over Spokane, Washington.[9] A full of iv to five in (100 to 130 mm) of ash cruel on Yakima, and areas every bit far e as Spokane were plunged into darkness by apex, where visibility was reduced to ten ft (3 m) and 0.5 in (xiii mm) of ash fell.[35] Continuing eastward,[38] St. Helens' ash fell in the western role of Yellowstone National Park by 10:15 pm, and was seen on the ground in Denver the side by side day.[35] In fourth dimension, ash autumn from this eruption was reported every bit far away equally Minnesota and Oklahoma, and some of the ash drifted around the world within about 2 weeks.

During the nine hours of vigorous eruptive activity, about 540,000,000 tons (540×10 ^ 6 short tons or 490×10 ^ vi t) of ash savage over an surface area of more 22,000 sq mi (57,000 km2).[9] The total volume of the ash before its compaction by rainfall was nigh 0.three cu mi (1.iii kmthree).[9] The volume of the uncompacted ash is equivalent to near 0.05 cu mi (0.21 km3) of solid rock, or nigh 7% of the amount of material that slid off in the droppings avalanche.[9] By effectually v:thirty pm on May 18, the vertical ash column declined in stature, merely less astringent outbursts continued through the next several days.[39]

Ash backdrop [edit]

Residue lateral blast effects in the channelized boom zone, some 30 years after the eruption: Harm ranged from scorched earth, through tree trunks snapped at various heights, to more than superficial effects.

Generally, given that the fashion airborne ash is deposited after an eruption is strongly influenced past the meteorological atmospheric condition, a certain variation of the ash blazon will occur, as a office of distance to the volcano or time elapsed from eruption. The ash from Mount St. Helens is no exception, hence the ash properties take large variations.[twoscore]

Chemical limerick [edit]

The majority chemic composition of the ash has been found to exist most 65% silicon dioxide, 18% aluminum oxide, 5% ferric oxide, four% each calcium oxide and sodium oxide, and 2% magnesium oxide. Trace chemicals were also detected, their concentrations varying as 0.05–0.09% chlorine, 0.02–0.03% fluorine, and 0.09–0.three% sulfur.[40]

Index of refraction [edit]

The index of refraction, a measure out used in physics to describe how light propagates through a particular substance, is an important property of volcanic ash. This number is complex, having both real and imaginary parts, the real part indicating how calorie-free disperses and the imaginary part indicating how calorie-free is absorbed past the substance.

The silicate particles are known to have a real alphabetize of refraction ranging betwixt 1.five and 1.6 for visible light. However, a spectrum of colors is associated with samples of volcanic ash, from very light to dark grayness. This makes for variations in the measured imaginary refractive alphabetize under visible light.[41]

In the case of Mount St. Helens, the ash settled in three main layers on the ground:[twoscore]

- The bottom layer was dark grey and was constitute to exist abundant in older rocks and crystal fragments.

- The middle layer consisted of a mixture of glass shards and pumice.

- The peak layer was ash consisting of very fine particles.

For example, when comparison the imaginary role of the refractive alphabetize one thousand of stratospheric ash from 9.iii and 11.2 mi (15 and 18 km) from the volcano, they accept similar values around 700 nm (around 0.009), while they differ significantly around 300 nm. Here, the eleven.2 mi (18 km) sample (1000 was institute to exist around 0.009) was much more than absorbent than the 9.3 mi (15 km) sample (k was found to exist around 0.002).[41]

Mudslides flow downstream [edit]

Mudline next to Muddied River from the 1980 lahars

The hot, exploding material also broke autonomously and melted nearly all of the mountain's glaciers, along with well-nigh of the overlying snowfall. As in many previous St. Helens' eruptions, this created huge lahars (volcanic mudflows) and muddy floods that affected three of the 4 stream drainage systems on the mount,[37] and which started to move as early every bit 8:l am.[33] Lahars travelled as fast as 90 mph (140 km/h) while still high on the volcano, but progressively slowed to about 3 mph (4.8 km/h) on the flatter and wider parts of rivers.[9] Mudflows from the southern and eastern flanks had the consistency of moisture physical as they raced down Dirty River, Pine Creek, and Smith Creek to their confluence at the Lewis River. Bridges were taken out at the rima oris of Pine Creek and the head of Swift Reservoir, which rose 2.half-dozen ft (0.79 m)[37] past apex to arrange the most 18,000,000 cu yd (14,000,000 grandiii) of boosted water, mud, and debris.[9]

Glacier and snowmelt mixed with tephra on the volcano's northeast slope to create much larger lahars. These mudflows traveled downwardly the northward and south forks of the Toutle River and joined at the confluence of the Toutle forks and the Cowlitz River near Castle Rock, Washington, at one:00 pm. Xc minutes after the eruption, the first mudflow had moved 27 mi (43 km) upstream, where observers at Weyerhaeuser'southward Camp Baker saw a 12 ft-high (four m) wall of muddied water and debris pass.[33] Near the confluence of the Toutle's north and southward forks at Silver Lake, a record flood stage of 23.5 ft (7.2 yard) was recorded.[33]

A large but slower-moving mudflow with a mortar-like consistency was mobilized in early afternoon at the head of the Toutle River northward fork. By two:thirty pm, the massive mudflow had destroyed Camp Baker,[33] and in the post-obit hours, 7 bridges were carried abroad. Function of the flow backed upwardly for ii.5 mi (4.0 km) soon after entering the Cowlitz River, just nearly connected downstream. Later traveling 17 mi (27 km) further, an estimated 3,900,000 cu yd (iii,000,000 g3) of fabric were injected into the Columbia River, reducing the river's depth by 25 ft (eight k) for a 4 mi (half-dozen km) stretch.[33] The resulting 13 ft (iv.0 one thousand) river depth temporarily closed the decorated channel to ocean-going freighters, costing Portland, Oregon, an estimated $5 one thousand thousand (equivalent to $16.4 one thousand thousand today).[39] Ultimately, more than than 65×10 ^ 6 cu yd (50×10 ^ half dozen grandthree; 1.viii×x ^ ix cu ft) of sediment were dumped forth the lower Cowlitz and Columbia Rivers.[ix]

Aftermath [edit]

Mount St. Helens one solar day earlier the eruption, photographed from the Johnston ridge

Mount St. Helens iv months after the eruption, photographed from roughly the same location as was the before picture: Note the barrenness of the terrain as compared to the image higher up.

Direct results [edit]

The May 18, 1980, issue was the nearly deadly and economically subversive volcanic eruption in the history of the contiguous U.s..[9] About 57 people were killed direct from the blast, and 200 houses, 47 bridges, 15 mi (24 km) of railways, and 185 mi (298 km) of highway were destroyed; two people were killed indirectly in accidents that resulted from poor visibility, and two more suffered fatal middle attacks from shoveling ash.[42] U.S. President Jimmy Carter surveyed the impairment, and said it looked more than desolate than a moonscape.[43] [44]

A film crew was dropped by helicopter on Mount St. Helens on May 23 to document the devastation, but their compasses spun in circles and they quickly became lost.[45] A 2d eruption occurred the next solar day (see below), but the coiffure survived and was rescued two days after that. The eruption ejected more 1 cu mi (4.2 km3) of material.[46] A quarter of that book was fresh lava in the class of ash, pumice, and volcanic bombs, while the residue was fragmented, older rock.[46] The removal of the northward side of the mount (13% of the cone's book) reduced Mountain St. Helens' meridian by nearly 1,300 ft (400 1000) and left a crater one to 2 mi (1.half-dozen to iii.two km) broad and 2,100 ft (640 g) deep with its north end open up in a huge alienation.[46]

More than four,000,000,000 lath feet (9,400,000 miii) of timber were damaged or destroyed, mainly by the lateral smash. At least 25% of the destroyed timber was salvaged after September 1980. Downwind of the volcano, in areas of thick ash accumulation, many agricultural crops, such as wheat, apples, potatoes, and alfalfa, were destroyed. As many as i,500 elk and 5,000 deer were killed, and an estimated 12 meg Chinook and Coho salmon fingerlings died when their hatcheries were destroyed. Another estimated twoscore,000 young salmon were lost when they swam through turbine blades of hydroelectric generators after reservoir levels were lowered along the Lewis River to accommodate possible mudflows and alluvion waters.[9]

In total, Mount St. Helens released 24 megatons of thermal energy, 7 of which were a direct result of the blast. This is equivalent to 1,600 times the size of the diminutive bomb dropped on Hiroshima.[47]

Disputed death toll [edit]

The expiry price most unremarkably cited is 57, but 2 points of dispute remain.

The first indicate regards two officially listed victims, Paul Hiatt and Dale Thayer. They were reported missing later the explosion. In the aftermath, investigators were able to locate individuals named Paul Hiatt and Dale Thayer who were alive and well. Yet, they were unable to determine who reported Hiatt missing, and the person who was listed as reporting Thayer missing claimed she was non the one who had done and then. Since the investigators could not thus verify that they were the same Hiatt and Thayer who were reported missing, the names remain listed amid the presumed dead.[48] [49]

The second indicate regards three missing people who are not officially listed as victims: Robert Ruffle, Steven Whitsett, and Mark Melanson. Cowlitz County Emergency Services Management lists them as "Possibly Missing — Non on [the official] Listing". According to Melanson'due south brother, in October 1983, Cowlitz Canton officials told his family that Melanson "is believed [...] a victim of the May 18, 1980, eruption" and that after years of searching, the family eventually decided "he'southward buried in the ash".[49]

Taking these two points of dispute into consideration, the direct death toll could be as low every bit 55 or as high as 60. When combined with the 4 indirect victims (two dying from vehicle accidents due to poor visibility, and two dying from middle attacks triggered past shovelling ash[42]) those numbers range from 59 to 64.

Ash damage and removal [edit]

Map of ash distribution over the U.s.a.

The ash fall created some temporary major issues with transportation, sewage disposal, and h2o handling systems. Visibility was profoundly decreased during the ash fall, endmost many highways and roads. Interstate 90 from Seattle to Spokane was closed for a week and a half. Air travel was disrupted for betwixt a few days and two weeks, as several airports in eastern Washington shut down because of ash aggregating and poor visibility. Over a g commercial flights were cancelled following airport closures. Fine-grained, gritty ash caused substantial problems for internal combustion engines and other mechanical and electrical equipment. The ash contaminated oil systems and clogged air filters and scratched moving surfaces. Fine ash caused short circuits in electrical transformers, which in plough caused power blackouts.[9]

Removing and disposing of the ash was a monumental task for some Eastern Washington communities. Country and federal agencies estimated that over ii,400,000 cu yd (1,800,000 m3) of ash, equivalent to nigh 900,000 tons in weight, were removed from highways and airports in Washington. The ash removal cost $2.2 million and took 10 weeks in Yakima.[9] The need to remove ash apace from ship routes and ceremonious works dictated the option of some disposal sites. Some cities used one-time quarries and existing sanitary landfills; others created dump sites wherever expedient. To minimize wind reworking of ash dumps, the surfaces of some disposal sites were covered with topsoil and seeded with grass. In Portland, the mayor somewhen threatened businesses with fines if they failed to remove the ash from their parking lots.[l]

Cost [edit]

One of the 200 houses destroyed by the eruption

A refined judge of $1.i billion ($3.4 billion as of 2018[update] [51]) was determined in a study by the International Merchandise Commission at the request of the U.s.a. Congress. A supplemental appropriation of $951 million for disaster relief was voted by Congress, of which the largest share went to the Small Business Administration, U.South. Ground forces Corps of Engineers, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency.[nine]

As well, indirect and intangible costs of the eruption were incurred. Unemployment in the immediate region of Mountain St. Helens rose ten-fold in the weeks immediately post-obit the eruption, and and then returned to almost-normal levels once timber-salvaging and ash-cleanup operations were underway. Simply a small per centum of residents left the region because of lost jobs owing to the eruption. Several months after May 18, a few residents reported suffering stress and emotional problems, though they had coped successfully during the crisis. Counties in the region requested funding for mental-health programs to help such people.[nine]

Initial public reaction to the May 18 eruption dealt a nearly crippling blow to tourism, an important industry in Washington. Non only was tourism downwardly in the Mount St. Helens–Gifford Pinchot National Forest area, merely conventions, meetings and social gatherings also were cancelled or postponed at cities and resorts elsewhere in Washington and neighboring Oregon not afflicted by the eruption. The adverse issue on tourism and conventioneering, however, proved but temporary. Mount St. Helens, perchance because of its reawakening, has regained its entreatment for tourists. The U.Due south. Forest Service and the Country of Washington opened visitor centers and provided admission for people to view the volcano's destruction.[9]

Later eruptions [edit]

St. Helens produced an additional five explosive eruptions between May and October 1980. Through early 1990, at to the lowest degree 21 periods of eruptive activity had occurred. The volcano remains active, with smaller, dome-edifice eruptions continuing into 2008.

1980–1991 [edit]

Eruption on July 22, 1980

An eruption occurred on May 25, 1980, at two:30 am that sent an ash column 9 mi (48,000 ft; 14 km) into the atmosphere.[46] The eruption was preceded by a sudden increase in earthquake activity, and occurred during a rainstorm. Erratic current of air from the storm carried ash from the eruption to the south and west, lightly dusting large parts of western Washington and Oregon. Pyroclastic flows exited the northern breach and covered avalanche debris, lahars, and other pyroclastic flows deposited by the May eighteen eruption.[46]

At seven:05 pm on June 12, a plume of ash billowed 2.v mi (four.0 km) above the volcano. At 9:09 pm, a much stronger explosion sent an ash column about 10 mi (16 km) skyward.[52] This event caused the Portland area, previously spared by current of air direction, to exist thinly coated with ash in the eye of the almanac Rose Festival.[53] A dacite dome then oozed into existence on the crater floor, growing to a height of 200 ft (61 m) and a width of i,200 ft (370 m) within a week.[52]

A series of large explosions on July 22 broke more than a month of relative repose. The July eruptive episode was preceded by several days of measurable expansion of the elevation expanse, heightened earthquake action, and changed emission rates of sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide. The first hit at 5:xiv pm as an ash column shot 10 mi (16 km) and was followed by a faster blast at six:25 pm that pushed the ash column in a higher place its previous maximum height in just 7.v minutes.[52] The final explosion started at 7:01 pm, and connected over two hours.[52] When the relatively small amount of ash settled over eastern Washington, the dome built in June was gone.[54]

The growing third dome on October 24, 1980

Seismic action and gas emission steadily increased in early August, and on August 7 at iv:26 pm, an ash deject slowly expanded 8 mi (13 km) into the sky.[54] Small-scale pyroclastic flows came through the northern breach and a weaker outpouring of ash rose from the crater. This connected until 10:32 pm, when a 2nd big blast sent ash high into the air, proceeding due n.[54] A 2d dacite dome filled this vent a few days afterwards.

Two months of repose were ended past an eruption lasting from October 16 to xviii. This outcome obliterated the second dome, sent ash x mi in the air and created small, red-hot pyroclastic flows.[54] A third dome began to class within xxx minutes after the final explosion on October 18, and within a few days, it was about 900 ft (270 grand) broad and 130 ft (40 g) high. In spite of the dome growth adjacent to it, a new glacier formed rapidly inside the crater.

All of the post-1980 eruptions were quiet dome-building events, beginning with the December 27, 1980, to Jan iii, 1981, episode. By 1987, the third dome had grown to be more iii,000 ft (910 1000) wide and 800 ft (240 1000) loftier.[54]

Further eruptions occurred over a few months between 1989 and 1991.

- Satellite images before and after 1980 eruption

-

Satellite prototype of Mount St. Helens crater (22 July 1982)

-

Satellite image of Mount St. Helens crater 30 June 1980 (color infrared)

-

Satellite paradigm of Mount St. Helens before eruption (23 July 1975)

Plume of volcanic ash and steam in the October 2004 eruption

2004–2008 [edit]

The 2004–2008 volcanic activity of Mount St. Helens has been documented every bit a continuous eruption with a gradual extrusion of magma at the Mount St. Helens volcano. Starting in October 2004, a gradual edifice of a new lava dome happened. The new dome did not rise above the crater created by the 1980 eruption. This activity lasted until Jan 2008.

- Elevation models and mural (lava domes) change models of Mount St. Helens (crater) betwixt 1982 and 2017

-

Digital peak model (DEM) of Mountain St. Helens (1982)

-

DEM of Mount St. Helens (2003)

-

DEM of Mountain St. Helens (2017)

-

Lava domes growth and landscape change of Mount St. Helens 2002-2017

-

Lava domes growth and landscape alter of Mount St. Helens 1982-2003

-

Lava domes growth and landscape change of Mount St. Helens 1982-2017

Summary table [edit]

| Eruption summary May xviii, 1980, eruption of Mount St. Helens | ||

|---|---|---|

| Superlative of meridian: | Earlier eruption: | 9,677 ft (2,950 m) |

| After eruption: | 8,363 ft (two,549 m) | |

| Total removed: | one,314 ft (401 m) | |

| Crater dimensions: | Eastward-W: | 1.2 mi (1.9 km) |

| North-S: | 1.8 mi (2.ix km) | |

| Depth: | 2,084 ft (635 one thousand) | |

| Crater floor superlative: | 6,279 ft (1,914 m) | |

| Eruption | Date: | May 18, 1980 |

| Time of initial boom: | 8:32 am Pacific Daylight Fourth dimension (UTC−7) | |

| Eruption trigger: | A magnitude-v.ane convulsion most 1 mi (i.6 km) below the volcano | |

| Landslide and debris barrage | Area covered: | 23 sq mi (60 km2) |

| Volume: (uncompacted deposits) | 0.67 cu mi (two.8 km3) | |

| Depth of deposit: | Cached North Fork Toutle River to average depth of 150 ft (46 m) with a maximum depth of 600 ft (183 yard) | |

| Speed: | seventy to 150 mph (113 to 241 km/h) | |

| Lateral blast | Expanse covered: | 230 sq mi (596 km2); reached 17 mi (27 km) northwest of the crater |

| Volume of deposit: (uncompacted deposits) | 0.046 cu mi (0.nineteen km3) | |

| Depth of eolith: | From about iii ft (1 chiliad) at volcano to less than one in (ii.5 cm) at blast border | |

| Speed: | At least 300 mph (480 km/h) | |

| Temperature: | As high equally 660 °F (350 °C) | |

| Energy release: | 24 megatons thermal energy (7 past blast, rest through release of rut) | |

| Trees blown down: | 4,000,000,000 board feet (9,400,000 grandthree) of timber (enough to build about 300,000 two-bedroom homes) | |

| Human fatalities: | 55-60 (direct); 4 (indirect); 59-64 (total) | |

| Lahars | Speed: | About 10 to 25 mph (xvi to 40 km/h) and over 50 mph (lxxx km/h) on steep flanks of volcano |

| Damaged: | 27 bridges, nearly 200 homes: Blast and lahars destroyed more than 185 mi (298 km) of highways and roads and 15 mi (24 km) of railways. | |

| Effects on Cowlitz River: | Reduced carrying chapters at flood phase at Castle Stone from 76,000 cu ft (2,200 chiliad3) per second to less than 15,000 cu ft (420 one thousand3) per 2nd. | |

| Effects on Columbia River: | Reduced channel depth from 40 to 14 ft (12 to 4 m); stranded 31 ships in upstream ports | |

| Eruption column and deject | Height: | Reached near eighty,000 ft (24,400 m) in less than 15 minutes |

| Downwind extent: | Spread across U.S. in 3 days; circled Earth in fifteen days | |

| Book of ash: (based on uncompacted deposits) | 0.26 cu mi (1.1 kmiii) | |

| Ash autumn area: | Detectable amounts of ash covered 22,000 sq mi (57,000 km2) | |

| Ash autumn depth: | x in (25 cm) at ten mi (sixteen km) downwind (ash and pumice) i in (2.5 cm) at 60 mi (97 km) downwind 0.five in (i.3 cm) at 300 mi (480 km) downwind | |

| Pyroclastic flows | Surface area covered: | half dozen sq mi (16 km2); reached as far as 5 mi (8 km) north of crater |

| Volume and depth: (volume based on uncompacted deposits) | 0.029 cu mi (0.12 km3); multiple flows 3 to xxx ft (ane to ix thou) thick; cumulative depth of deposits reached 120 ft (37 m) in places | |

| Speed: | Estimated at 50 to 80 mph (80 to 130 km/h) | |

| Temperature: | At least ane,300 °F (700 °C) | |

| Other | Wildlife: | The Washington Country Department of Game estimated nearly seven,000 big game animals (deer, elk and bear) perished as well as all birds and most modest mammals. Many burrowing rodents, frogs, salamanders and crawfish managed to survive considering they were below ground level or water surface when the disaster struck. |

| Fisheries: | The Washington Department of Fisheries estimated that 12 1000000 Chinook and Coho salmon fingerlings were killed when hatcheries were destroyed. Another estimated twoscore,000 young salmon were lost when forced to swim through turbine blades of hydroelectric generators as reservoir levels along the Lewis River were kept depression to accommodate possible mudflows and flooding. | |

| Brantley and Myers, 1997, Mount St. Helens – From the 1980 Eruption to 1996: USGS Fact Canvass 070–97, accessed 2007-06-05; and Tilling, Topinka, and Swanson, 1990, Eruption of Mount St. Helens – Past, Present, and Future: USGS Full general Involvement Publication, accessed 2007-06-05. | ||

| Tabular array compiled by Lyn Topinka, USGS/CVO, 1997 | ||

See also [edit]

- Cascade Volcanoes – High Cascades

- The Eruption of Mount St. Helens! (1980 film) – documentary flick about the eruption

- St. Helens (1981 motion-picture show) - television picture show about the eruption

- Geology of the Pacific Northwest

- Helenite – An artificial glass marketed equally a gemstone, made past fusing the volcanic dust from Mount St. Helens' May 1980 eruption

- List of Cascade volcanoes

- Listing of volcanoes in the The states

- Pacific Ring of Fire

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b "St. Helens". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Establishment. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ Fisher, Heiken & Hulen 1998, p. 294.

- ^ "USGS M 5.7 Mt. St Helens convulsion trigger". earthquake.usgs.gov . Retrieved May eighteen, 2020.

- ^ "What was the largest landslide in the Usa? In the world?". www.usgs.gov . Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Harden, Blaine (May 18, 2005). "Explosive Lessons of 25 Years Ago". The Washington Post. p. A03. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ Short, Dylan (March 19, 2019). "U of A researchers looking for Albertans who experienced volcano". edmontonjournal.com. Edmonton Journal. Retrieved May i, 2019.

dust was found most heavily in the foothills area in southern Alberta, only may have drifted equally far n as Scarlet Deer.

- ^ "Mount Saint Helens Eruption - giph.io". giph.io. Archived from the original on September 26, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- ^ "Those who lost their lives because of the May 18, 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens" (PDF). KGW news. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j m 50 m n o p q r south t u 5 w 10 y z aa ab ac advertizing ae af Tilling, Robert I.; Topinka, Lyn; Swanson, Donald A. (1990). "Eruptions of Mount St. Helens: Past, Present, and Future". U.S. Geological Survey (Special Involvement Publication). Archived from the original on October 26, 2011. Retrieved Dec v, 2010. (adjusted public domain text).

- ^ Runte, Alfred (1983). "Burlington Northern and the Legacy of Mount St. Helens". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly. 74 (three): 116–123. ISSN 0030-8803. JSTOR 40490550.

Burlington Northern, as co-possessor of Mount St. Helens with the federal regime, was especially concerned most the future of the peak, [...] Extending from the lip of the crater down the slopes opposite the blast area, arcing ninety degrees from due due south to due west, lay the remainder of the square mile that originally had formed part of the [Northern Pacific Railroad's 1864] country grant. Clearly, this portion of the mount had no commercial utilise but great value as the nucleus of the national park or monument already proposed by ecology groups. In recognition of the popularity of these proposals, Burlington Northern in 1982 restored the area to the federal government.

- ^ Gorney, Cynthia (March 31, 1980). "The Volcano: Full Theater, Stuck Curtain; Hall Packed for Volcano, But the Mantle Is Stuck". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b "Mount St. Helens Precursory Activity: March 15–21, 1980". USGS. 2001. Archived from the original on October half dozen, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Harris 1988, p. 202.

- ^ Ray, Dewey (March 27, 1980). "Oregon volcano may be warming upwardly for an eruption". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved Oct 31, 2010.

- ^ a b "Mount St. Helens Precursory Activity: March 22–28, 1980". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on Oct v, 2012. Retrieved June vi, 2015.

- ^ "Mount St. Helens blows its top". Lewiston Forenoon Tribune. Associated Press. March 28, 1980. p. 1A.

- ^ Rose, Robert L. (March 28, 1980). "Washington volcano blowing its superlative". The Spokesman-Review. p. 1.

- ^ Blumenthal, Les (March 29, 1980). "Hot volcanic ash moves lower". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Printing. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Harris 1988, p. 204.

- ^ a b c d Harris 1988, p. 203.

- ^ a b "Mount St. Helens Precursory Activity: March 29 – April 4, 1980". United states Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on October x, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ "Hazard zones created around mountain". The Spokesman-Review. Associated Press. May 1, 1980. p. 8.

- ^ a b "Volcano bulge grows". Spokane Daily Chronicle. UPI. May 2, 1980. p. 6.

- ^ "Mountain St. Helens cabin owners aroused at ban". Spokane Daily Chronicle. wire services. May 17, 1980. p. 1.

- ^ "Mount St. Helens Precursory Activity: April 5–eleven, 1980". The states Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ "St. Helens: Huge hunk of mountain could still striking lake". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Associated Press. Apr 29, 1980. p. 3B.

- ^ a b "Reawakening and Initial Action". Us Geological Survey. 1997. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- ^ "Mount St. Helens Precursory Activeness: May 3–9, 1980". USGS. 2001. Archived from the original on February 3, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2007.

- ^ a b c "Mountain St. Helens Precursory Activity: May x–17, 1980". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Archived from the original on March 12, 2010. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ^ a b "Homes nearly volcano checked". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Printing. May 18, 1980. p. 6A.

- ^ a b c d e Harris 1988, p. 205.

- ^ Fisher, Heiken & Hulen 1998, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris 1988, p. 209.

- ^ Fritz, William, J.; Harrison, Sylvia (1985). "Transported copse from the 1982 Mount St. Helens sediment flows: Their use every bit paleocurrent indicators". Sedimentary Geology (scientific). 42 (1, 2): 49–64. Bibcode:1985SedG...42...49F. doi:10.1016/0037-0738(85)90073-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris 1988, p. 206.

- ^ Robert Coenraads (2006). "Natural Disasters and How We Cope", p.50. Millennium House, ISBN 978-1-921209-xi-6.

- ^ a b c Harris 1988, p. 208.

- ^ "Cloud of ash soaring over Kentucky". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Press. May xx, 1980. p. 5A.

- ^ a b Harris 1988, p. 210.

- ^ a b c Taylor, H. E.; Lichte, F. E. (1980). "Chemical composition of Mount St. Helens volcanic ash". Geophysical Inquiry Messages. 7 (11): 949–952. Bibcode:1980GeoRL...7..949T. doi:ten.1029/GL007i011p00949.

- ^ a b Patterson, East. M. (1981). "Measurement of the Imaginary Part of the Refractive Index Betwixt 300 and 700 Nanometers for Mount St. Helens Ash". Scientific discipline. 211 (4484): 836–838. Bibcode:1981Sci...211..836P. doi:10.1126/science.211.4484.836. PMID 17740398.

- ^ a b "What were the effects on people when Mt St Helens erupted?". Oregon State University. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

- ^ Patty Murray (May 17, 2005). "25th Ceremony of the Mountain St. Helens Eruption". Congressional Record – Senate. U.S. Regime Printing Function. p. S5252. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Egan, Timothy (June 26, 1988). "Trees Return to St. Helens, But Practice They Make a Forest?". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved May 18, 2009.

- ^ Michael Lienau. "To Touch a Volcano: A Filmmaker's Story of Survival". Global Net Productions. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011. Retrieved May nineteen, 2009.

- ^ a b c d eastward Harris 1988, p. 211.

- ^ "Mountain St. Helens – From the 1980 Eruption to 2000, Fact Sheet 036-00". U.South. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

- ^ Slape, Leslie (Apr 22, 2005). "Mountain Mystery: Some wonder if fewer people died in 1980 eruption". The Daily News . Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ a b "Mt. St Helens Victims". The Columbian . Retrieved Dec 10, 2015.

- ^ Painter, John Jr. The 1980s. The Oregonian, December 31, 1989.

- ^ Equally calculated using "Inflation Calculator". Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Harris 1988, p. 212.

- ^ "He Remembers the Twelvemonth the Mountain Blew (1980)". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved January 28, 2008.

- ^ a b c d east Harris 1988, p. 213.

Sources [edit]

-

This commodity incorporates public domain material from the United States Geological Survey document: "Eruptions of Mountain St. Helens: By, Present, and Futurity". Retrieved Dec 5, 2010.

This commodity incorporates public domain material from the United States Geological Survey document: "Eruptions of Mountain St. Helens: By, Present, and Futurity". Retrieved Dec 5, 2010. - Fisher, R. Five.; Heiken, G.; Hulen, J. (1998). Volcanoes: Crucibles of Alter. Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0-691-00249-1.

- Harris, Stephen L. (1988). Burn Mountains of the W: The Pour and Mono Lake Volcanoes . Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company. ISBN978-0-87842-220-3.

- Klimasauskas, Ed (May ane, 2001). "Mountain St. Helens Precursory Action". Us Geological Survey. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- Tilling, Robert I.; Topinka, Lyn; Swanson, Donald A. (1990). "Eruptions of Mountain St. Helens: Past, Present, and Future". U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on Oct 26, 2011. Retrieved December 5, 2010. (adjusted public domain text)

- Topinka, Lyn. "Mount St. Helens: A General Slide Prepare". Cascades Volcano Observatory, U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on December eighteen, 2007. Retrieved May x, 2007.

Further reading [edit]

- "Eruption of Mountain St. Helens". National Geographic. Vol. 159, no. 1. January 1981. pp. 3–65. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- Findley, Rowe (Dec 1981). "Mount St. Helens Backwash". National Geographic. Vol. 160, no. 6. pp. 713–733. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links [edit]

- "Mt. St. Helens Volcano Victims". I Dream of Genealogy. Archived from the original on May 27, 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2004.

- Listing of victims with biographical details

- USGS: Mountain St. Helens 1980 Debris Barrage Eolith

- USDA Forest Service: Mount St. Helens VolcanoCam

- Pre-1980 Eruptive History of Mount St. Helens, Washington

- USGS: Before, During, and After May eighteen, 1980

- Video approximation of the offset seconds of the May xviii eruption from Gary Rosenquist's photos on YouTube

- Boston.com – The Big Picture – 30 years later

- The short film Eruption of Mount St. Helens, 1980 (1981) is bachelor for gratis download at the Cyberspace Archive.

- The short moving picture This identify in time: The Mount St. Helens story (1984) is bachelor for gratuitous download at the Cyberspace Annal.

- Aerial pictures of the July 22nd, 1980 secondary eruption

- News reports Archived December 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine at The Museum of Classic Chicago Television

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1980_eruption_of_Mount_St._Helens

0 Response to "When Did Mt St Helens Erupted When Will Mt St Helens Erupt Again"

Post a Comment